So here is a story I was once told. It is not a story for you to believe or disbelieve. Ultimately it doesn’t even matter what we believe. What matters is how those beliefs affect us, our communities, and the earth we stand on. This is a story simply to read and feel.

In the beginning of time there was a mother. Without her there was nothing. She came before life and death, being and not being, and was of something far higher than that, and so it was she who created life and death. As she was a being of pure love, the source of creation, it was not so black and white as living and dying, but rather those two were intertwined in a very unique journey, a journey from pure consciousness, through to the dimensions of physical matter, and back to metaphysical being. Life, being itself not so simple, took many forms. It was fuelled by the elements of creativity, curiosity, and of course survival, for life as a concept is something of a trickster. It is an experience so unique that whomever comes across it wishes very deeply to hold on to some part of it. And so this is how life continued. Life evolved; an act derived from a deep love for itself.

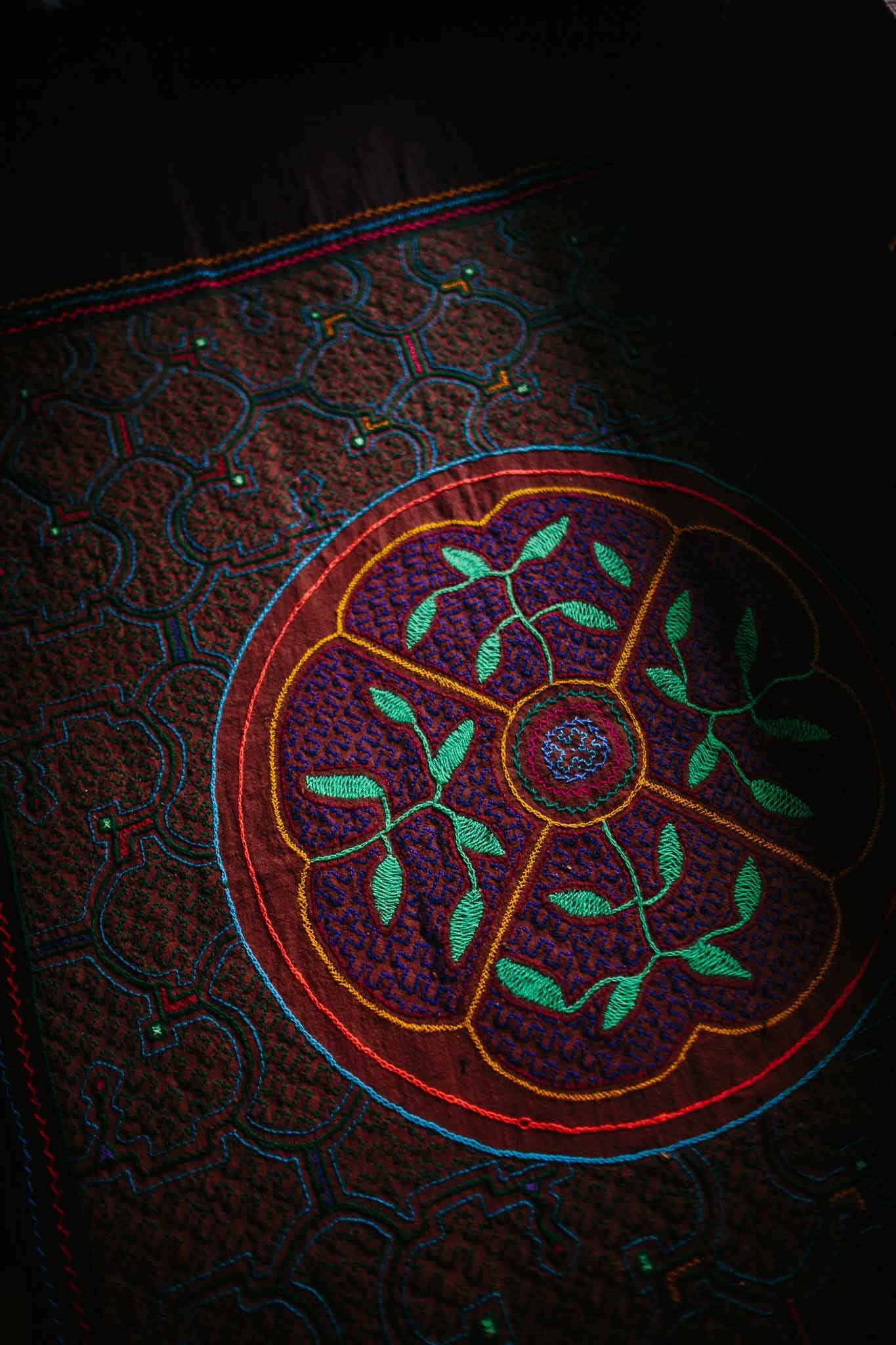

The mother watched as it unfolded, knowing that the experience of life she had seeded, though beautiful and seductive to those who lived it, was only a small thread of the great tapestry of being. It did not begin with life, nor did it end in death; for it was fused with consciousness, which itself has no boundaries in space and time. And there was yet another piece, even closer to the essence of the mother’s pure being and indeed a gift from her own; there was soul. It was soul who wove its way between all the cycles of life and death, the fear and anger, the pain and suffering, the beauty and fulfillment, and the love that lay at the heart of it all. It was soul who told the tales of life both within the physical realm and other realms far beyond. Together the stories of many souls joined into a great ocean, an ocean full of beautiful, incredible, and terrifying tales of life’s journey through matter and consciousness. In this ocean the mother bathed, washing herself with the stories of the soul which was her own. In the chorus of the soul’s song could be heard a great purpose, for the mother had planted the seed of her divinity inside of her experiment.

So life at first, attached as it was to itself (and to death; it’s mirror), did not remember where it came from. Yet in each whisper of experience there was an echo of the great journey. Each moment contained symbols of a love eternal, so vast that all things were contained within it. As life grew in it’s complexity and creativity, it began to discover itself more deeply. It began to follow the signs from the soul of the earth, which was itself the mother of existence on the physical plane. As life awoke, death’s softly spoken message became clearer. It was a voice of reassurance, and it said that death is but a shadow, for life never ends.

But even this softly spoken promise was hard to understand for those who lived life, and so time and again life thrust itself to the edge of it’s own percieved downfall, recoiling in it’s fear and distaste, not able to see that some loved life so much that they were too afraid to lose it. In their fear, they held on too tightly and brought all that they believed in to near destruction. It was then that the mother began again to remind life more clearly of it’s true essence, that of love eternal. Love, being the source of all creation, preceded fear, preceded pain and suffering, preceded life and death, and so contained all within it. Through the mirror of itself, life was able to reconcile with death. In the end, life came to recognize that it had never been only a physical experience, but a spiritual journey of coming to understand the truth of it’s being. Life was never more than a gift and an opportunity, a game to play should one choose it, a unique journey of soul in a physical dimension, creating and destroying, living and learning, and upon finally awaking; returning home to the mother.

In this story, the mother is not saving her creation, but rather teaching it what it means to have body and soul. It is about life coming to understand how incredible it is, and remembering that it comes from something yet even more incredible. Most of all, it suggested that life existed with a spiritual purpose of self-realization. As life realized it’s true self, it came to see that this ‘self’ was the love which contained all things.

Elements of this story probably sound very familiar to some. It may seem poetic, or even cheesy to others, hearing a story that suggests the great God-like mother is nurturing us on a physical, emotional, and spiritual level. Yet the further we step back, outside of a human-centric line of vision, the more we can perceive of the power of such a mythic idea. Those same people who would call it poetic or cheesy are possibly failing to recognize that they are masking an essential piece of what it means to be human. These are things that pull hidden pieces of us, prompting us to question what it is to be, and so find myriad forms of spirituality and mediums of artistic expression.